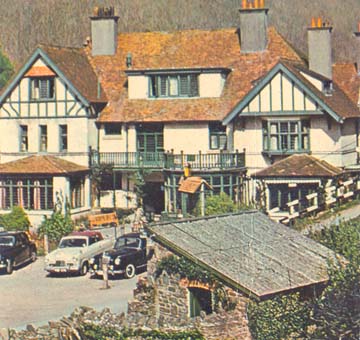

The author's mother, Pat Lorange, and grandfather, Bill Cook, with Alex Lorange's (the author's father's) 1957 Mercedes-Benz Type 219 Ponton sedan. Surrey, England, 1960. The crests are membership badges. Alex was a member of the Royal Automobile Club of Great Britain and the Club Automobile de Belgique.

There are two Mercedes-Benz vehicles in my memories. The one my father owned and the one I owned. The one that takes up the greatest amount of trunk space up there is my dad's 1957 Type 219 Ponton sedan.

I loved that car. Almost as much as he did, I suppose. He bought it in July or August 1957. My family had just left Cuba and was about to begin a chapter in Belgium. (He worked for U.S. Rubber, later named Uniroyal; the firm had just bought Englebert, a Belgian tire manufacturer; he was to work at the Englebert offices in Liège, in the French-speaking part of Belgium, for six years).

My brother and I were kids in 1957. Kirk was 8, I was 9.

We spent that summer in England, with my mother. We were visiting mother's

parents and preparing for the move by taking French lessons. Dad had gone

ahead and begun work in Liège. He'd always wanted to own a Mercedes-Benz.

Now that we were living in Europe, he reasoned, he'd buy one, right at

the factory. And that's what he did.

He would phone us, Belgium to England. At some point a date was set and

a plan was devised: He'd drive the new car from Liège to Ostend, on

the Belgian coast, take the ferry to Dover, England, and motor to Surrey where

mother and Kirk and I were staying. I forget when he said we could expect

him, but I remember that Kirk and I were down on the street hours ahead

of time, eyes peeled, scanning the approach from Dover for dad's new Mercedes-Benz.

It's black, he'd told us.

At that time, 12 years after the war, rationing barely over, there were

no German cars in England. (In fact, I remember asking my parents what one

of my grandparents' friends had meant, when he said that he wouldn't own

a Mercedes-Benz, "on principle.") Kirk and I saw no other Mercedes-Benz on

Wallington Road until we saw dad's. He high-beamed us and then - great big

smiles on all three faces - he pulled up alongside us.

Oh! Love at first sight. I suppose we could tell that he was thrilled with

it and I suppose in those days we emulated everything he did. We could barely

wait to go for a ride. We absolutely didn't see the necessity of his going

in to greet mother and granny and grandpa before taking us for a spin. Eventually

the six of us went for a ride (half as much fun as just the three of us) and

dad took great pleasure in showing us every one of the car's features, attractions

and benefits. At the destination, fenders were dusted, photos were taken,

a restaurant table from which the car could be admired was chosen, and so

on. Dad's new baby.

Within a matter of days the four of us left my mother's parents' place

and drove to Spa - yes, Spa as in Spa-Francorchamps, of motor-racing

fame - where we were to live. It was the first of several cross-channel motor

trips that we'd take in the Mercedes-Benz. Later Patti, born in 1961, was

part of the expeditions.

On the continent, German cars were numerous. We saw Mercedes-Benz vehicles

of all types. We soon realized that virtually every taxi in Belgium was

a black 180D or 190D, and there were pre-WWII models, 219s, 220s, 220Ss and

SEs, big Type 300 limousines, no-nonsense ambulances, pretty little 190SLs,

even a few heart-stoppingly muscular-looking 300SLs (every summer in the

weeks leading up to the Belgian Grand Prix, Spa was a magnet for exotic automobiles).

Kirk and I became proficient at spotting the telltale differences between

the look-alike sedans: "It's a 220." "No, it's an SE." "Oh, yeah."

There was a lot of talk about the best Mercedes-Benz color. Mother and I

favored what we called the "cherry red," not to be confused with the "deep

red." Kirk liked the metallics, rare at the time. Dad stuck to black. One

summer there were three 6-cylinder Pontons on our little street in Spa (two

of the houses were only occupied in the summer). But Kirk and I could still

tell, by ear, when it was dad driving up the hill at the end of the day.

He shifted gears differently than the neighbors' dads did. He had an "aural

signature" behind the wheel that his sons could read.

It's interesting that Bob Graham points out the diesel-only reminder on

his 190D fuel cap, because the opposite

blunder once happened to my dad. He pulled into a gas station in Spa (not

his usual station) for a fill-up, started driving home, and almost right

away noticed a change in the car's performance and saw thick smoke in the

rear-view mirror. He immediately and correctly deduced that the station attendant

had absent-mindedly figured his black 219 to be a taxi and filled it with

diesel fuel. He pulled over to the shoulder and shut the engine off. He walked

back to the gas station and described what had happened. They sent a truck,

towed the car to the station, drained the tank, flushed the tank, the line,

the engine. I seem to remember that the car was there for a couple of days.

I remember him being driven home in the tow-truck.

The family went several times to the inn where mother and dad had spent

their honeymoon, in Devon, in the south of England. (He was a Canadian soldier

who met and married a British girl. He was an army signalman and she a switchboard

operator. They met during the Battle of Britain on a crossed line -

a wrong number, in other words.)

One year we noticed that there was a new picture postcard of the inn, which is called The Hunters Inn. The sky in the photo was clear and blue, just as it had been during much of our previous visit. The trees were in early leaf, just as they'd been that time. There were a couple of cars in the parking lot in the photo, the lot where dad preferred to park. And "Hey, look!" - our Mercedes was in the photo! We were certain it was ours - not only was it left-hand drive, but one of the fog lamps was paler than the other. A flying pebble had broken one of dad's on the way home from work one night and he'd replaced it. The new one was a slightly deeper yellow. A detail of the card is shown here. In the parking lot, alongside the Ponton, are two staunch mid-1950s British "motors": a Rover 75 and a Ford Zephyr convertible.

When dad bought the car it had a rigid star (on the grille). Somehow or other the star got damaged. The replacement (he didn't drive it any longer than necessary with a broken star) was a safety-conscious "sprung" star - one that folds back on impact. The "evolved" star was introduced during the era of our 219 sometime between 1957 and 1962.

Another memory: In stalled traffic one day in Liège,

dad nudged the fellow ahead of us. Very gentle bumper-to-bumper contact.

The guy was driving a Panhard, as I recall, a homely-looking French car that

had all the appeal of a jelly mold on wheels. He jumped out of the car, came

back to look at his rear bumper. We got out too - dad and Kirk and I. There

was no trace of damage to either car. Zero. And yet Monsieur Panhard started

gesticulating and speaking loudly: "Non, mais, monsieur, vraiement, "Çest

pas normal..." Et cétéra. Dad, who was a good nine or ten inches

taller than him (and wearing a bold madras-cotton sports jacket, just possibly

the only one in Belgium), started out in careful French (he never mastered

it), but then thought, Never mind that, and simply let the guy have it in

English: "That's what bumpers are for, for God's sake," heavy emphasis on

the first "for." Then, with a "C'mon, boys," he turned away and got back

behind the wheel. Traffic still didn't move, raised voices notwithstanding.

Kirk and I laughed. Dad gave a sort of "I mean, really!" snort. Monsieur

Panhard glared.

In 1963 we left Belgium and moved to Canada and brought the 219 with us.

There weren't many Mercedes-Benz vehicles in Canada at the time. He drove

the 219 through two Montreal summers no problems - and two Montreal winters

- big problems. The car had a rudimentary heater, and it behaved poorly on

ice and snow. It had never been rust proofed, either. The tons of salt that

Ville de Montréal dumps on the streets began to have their way with

the car. "Rust never sleeps," said Neil Young, and he should know, he's

Canadian. In 1965 dad sold the Ponton.

In 2002 I was driving through Old Montreal and saw a beautifully restored

black 219 parked on rue St-Jacques. I stopped, parked, crossed the street

to look at this artifact from my childhood. I walked around it, looked in,

admired it for several long minutes. It was flawless from any distance. Toothpick-clean,

a joy to behold. It had US plates, I forget which state, but it had a km/h

speedometer - it was a European model. Could it be dad's? I wondered.

I was hoping the owner would show up, but I had an appointment and had

to leave. I took one last glance at it, in the rear-view mirror, as I headed

west. It was like driving away from a dream.